|

|

Serge Guilbaut, Joni Low, and Pan Wendt

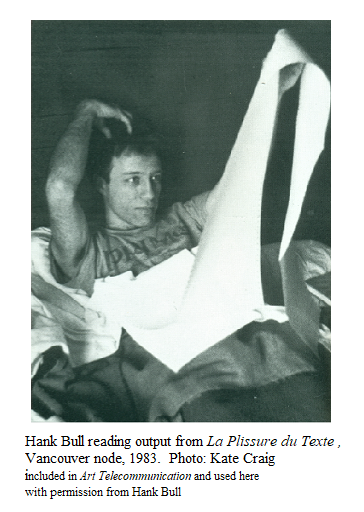

"What this midden offers is an analogue of our networked presence -- and its fragmented, irregular social formations and communications, which we are only beginning to understand. Immersed in a cacophony of information, media, and interactions daily, we must intuit what to focus on, derive meaning from, and connect with -- and engage with the world on that basis" -Joni Low in Hank Bull: Connexion The exhibition, Hank Bull: Connexion was based on Vancouver-situated artist Hank Bull's archives, collected beginning in the early 1970's and displayed by the artist himself in 2012 at the artist-run center for contemporary art and new music, Western Front. In 2015, curated by Joni Low and Pan Wendt, Hank Bull: Connexion was installed at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada. From January 20 to April 6, 2017, Hank Bull: Connexion returned to Vancouver, BC, Canada, where it was installed at the Burnaby Art Gallery. Hank Bull's work resides at the intersection of painting, sculpture, music, performance art, video, sound, radio, and telematic art. Beginning in the 1970's, he was associated with Western Front, and in 1999, he was a co-founder of the Vancouver-based International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Centre A). In the second decade of the 21st century, where the darker sides of global contemporary social media dominate discourse, the catalog for Hank Bull: Connexion -- infused with images and texts from his work and philosophies, as well as containing primary essays in both French and English by Serge Guilbaut, professor of art emeritus at the University of British Columbia; independent curator and writer Joni Low; and Pan Wendt, curator at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery -- provides an entry way for revisiting artists' projects in the formative years of social networking. "Networking as a mode of being manifests itself throughout Bull's practice, through collaboration, telecommunications art, and Filliou's idea of the Eternal Network, which Bull's material history so vividly expresses." -- Joni Low in Hank Bull: Connexion Interactive approaches to radio were a starting point for Bull's work with communications, but from a Networked Projects in the Formative Years of the Internet point of view, the story begins when he began working on artist-centered telecommunication projects in the 1970's, utilizing slowscan, electronic text, and fax. In the 1980's, using Canadian carrier I.P. Sharp's ARTEX platform, he was a core participant in projects such as Roy Ascott's La plissure du texte (1983), a collaborative fairy tale written in English and French by nodes including Vancouver, Sydney, Vienna, Amsterdam, Bristol, Boston, Pittsburgh, New York, San Francisco, and Honolulu, among others. "The Magician," British artist Roy Ascott, was at that time based in Paris. As the narrative progressed from node to node, an improvised, collaboratively-created text emerged. La plissure du texte was documented in the exhibition Hank Bull: Connexion with a printout bound in string. The catalog situates material from the exhibition in a click-bait-reminiscent array of entryways to Bull's work that suggests multiple interpretations and in the process, explores the roots of social networking in artist-centered communication circles. Beginning with the HP Dinner Show, (radio, with Patrick Ready, 1976-1984), in the catalog, an "Illustrated Chronology" by Bull himself sets forth projects such as Telephone Portraits (Taki Sekiguchi and others, 1977); Canada Africa 1.1 (conceived by Robert Filliou,1983); and Weincouver IV (Robert Adrian, Hank Bull, and others, 1983). "...a collapse of the proscenium arch separating actor from audience..." - Hank Bull in Social Media Archeology and Poetics Along the way, Hank Bull himself was a core creator of global projects, such as Shanghai Fax (1996), which he, Shi Yong, Shen Fan, and Ding Yi organized at the gallery of the Hua Shan College of Art. In his chapter in Social Media Archeology, Bull addresses the nature of the "audience" in telematic art projects. "As we see in the Internet today," he observes, "there was a collapse of the proscenium arch separating actor from audience, producer from consumer. Access to the tools of telecommunication, like the access to video that preceded it, enurtured hopes for democracy, a sense of being able to 'talk back to the media' and spawned an alternative economy of symbolic exchange outside the market." [1] Additionally, foreshadowing the role of social media in global politics -- such as the 2008 Facebook Group Un Millon de Voces Contra Las FARC or the Iranian voices on Twitter in protest of the 2009 Iranian presidential election -- in his chapter in Social Media Archeology and Poetics Bull describes how an "Art's Birthday" celebration evolved into networked protest. "In 1991, we faced the imminent possibility of war in Iraq. Karel Dudasek, of Ponton Media, had stationed himself in a hotel room in Amman, Jordan, equipped with a videophone. By a tragic twist of fate, just as everything was ready for our January 17th transmission, the bombing of Baghdad started. While millions sat stunned before their TVs, mesmerized by the spectacular and highly theatricalized representation of horrific events, the Art's Birthday network was immediately transformed from party to war protest. We found ourselves -- some twenty nodes, from Tucson to Tokyo -- operating our own independent global media network, with live reporting from Amman relayed and a street protest in Pittsburgh beaming back." - Hank Bull, Social Media Archeology and Poetics. [2] "The role Hank Bull often played within this milieu was that of a host, a person who produces a setting, a loose structure for the exchange of ideas, and who acts as a mediator or conduit between personalities." -- Pan Wendt in Hank Bull: Connexion The role of "host" in early nonprofit social media was, in many cases, conceived differently from the role of "moderator" in that there was no censorship or hierarchical consideration of participation in the idea of host. Ideally, a host welcomed and facilitated democratic discourse. However, varied interpretations of the-role-of or the-need-for "hosts", were, are, and will continue to be areas to review and discuss as we look to the future of social media. For instance, in a larger sense of "host", in many of the projects initiated by the Electronic Cafe -- such as at the 1984 Olympics, where diverse communities were linked in cafes across Los Angeles -- Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz could be considered the hosts, in that they provided the technology and created the environment. The same could be said of contemporary social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter. However, they are large commercial entities, whereas The Electronic Cafe was an artist-run project. For ARTEX, the Canadian time-sharing telecommunications carrier I.P. Sharp (IPSA) provided the technology, but projects were initiated by the artists themselves who served as host for various projects. A model was Bill Bartlett's 1979 Interplay, carried by IPSA, as a part of the Computer Culture Exposition at the 1979 Toronto Super8 Film Festival. During Interplay, from node to node, artists in Canberra, Edmonton, Houston, New York, Toronto, Sydney, Vancouver, and Vienna discoursed on future roles of computer culture, and, as the discussion progressed, computer printouts of their dialogue appeared in the participating cities. Other artist-hosted projects hosted by IPSA included Robert Adrian X's The World in 24 Hours (1982); and Norman White's hearsay, a tribute to Hungarian-born poet Robert Zend, in which, following the sun, a text was sent around the world in a 24-hour time-based event (1985). Hank Bull not only was a core participant in many of these projects but also served as a host/catalyst to inspire and provide platforms for projects on other systems. Beginning in 1985, on The WELL, there were various levels of overall management, but conferences were hosted by individuals (or, in the case of Art Com Electronic Network, an organization). For instance, techno-journalist Howard Rheingold developed and hosted The Mind Conference. SRI International futurist Tom Mandel developed and hosted the Future Conference. As the WELL notes on its website: "Hosting in the conversational sense is online innkeeping — a large part of what makes a sense of context and "place" worth coming back to again and again in the glistening, fragmented wasteland of the Web. Designating an informed, opinionated and outgoing conference host who is focused on encouraging interaction with a light touch, without censorship of ideas or language, is part of the magic of The WELL." [3] In the 1990's, on Arts Wire there was also an overall management that provided the technology and the environment, and, in an overall sense, hosted "interest groups" that were proposed, developed, and hosted in different ways by different individuals or organizations. For instance, AIDS and LGBT activist Michael Tidmus developed and maintained AIDSwire. Composers Pauline Oliveros, Douglas Cohen, and David Mahler hosted NEWMUSNET, a virtual space that centered on issues about/for composers, performers and presenters of experimental music and served as an incubator for new ensembles and new works. Anna Couey and I developed and hosted INTERACTIVE, an online laboratory for focused discussion and production of interactive art. Funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation, the NATIVE ARTS NETWORK ASSOCIATION (NANA), a group of Native Arts Organizations, had core involvement from Atlatl in Phoenix. PROJECTARTNET -- created in 1993 by Aida Mancillas and Lynn Susholtz -- was a San Diego-based community arts networking project that brought children from schools in immigrant neighborhoods online to create a community history. In the same era, Wolfgang Staehle served as the catalyst, as provider of technology, and as the overall manager for THE THING. THE THING began in New York City. Nodes followed in Cologne, Berlin, Vienna, London, Stockholm. Under THE THING's umbrella, an amazing array of projects that ranged from 9 Sculptures, New York, an online art project by Helene von Oldenburg with "floor maps of nine New York Museums and a legend indicating dimensions and location of nine imaginative sculptures in these spaces"; to Felix Huber and Philip Pocock's Arctic Circle, in which performance videos and sound loops were produced in the Arctic Circle; to the postcolonial BindiGirl web project by Prema Murthy, in which Murthy's avatar juxtaposed her own images with images from ancient Indian texts. [4] On contemporary commercial social media, the richness of content and dialogue that existed on early social media systems is there, but it is often diluted and difficult to find. Additionally, in defense of contemporary social media platforms, it should be noted that we don't see many big media outlets in other broadcasting systems (television, for instance) offering free platforms with a potential for equality to everyone in the world. Nevertheless, not only should the issues of Big Social Media as monopoly hosts in the provide-the-technology-and-the-environment/interface sense be debated, but also there is a need to incubate nonprofit alternatives where management does not own or misuse content -- particularly in the arts, where censorship is seldom appropriate, and unseen algorithmic censorship is insidious.

If this were an in-depth essay on the roles of hosting/moderation/management in profit as opposed to nonprofit social media platforms, this would be the time to examine this issue from the point of view of (for instance) Facebook groups, Twitter hashtags, and management's algorithic control of content. Meanwhile, what is core in this review is that publications such as the catalog for Hank Bull: Connexion, as well as Bull's extraordinary archives themselves, are vitally important in such discussions because they allow us to look not only at art history per se but also at the models that both individuals and organizations developed in the nonprofit era of social networking. "Follow the clues..." In "Style de vie", the concluding section of Hank Bull: Connexion, Joni Low, Alex Muir, and Pan Wendt arrange a series of images and lexias (in both English and French) that ground the exhibition and catalog in conversations in Hank Bull's apartment at Western Front during the years that led up to these events. The wind dislodges and breaks Yuxweluptun Lawrence Paul's wooden sculpture (made for the roof of Western Front at Hank Bull's request), and the sculptor’s surprising reaction is remembered; noise makers of all kinds are strewn on top of a piano, eliciting discussions of noise, music, and telematic communication; "Stories intermix and misunderstandings become openings for reinterpretation. Humans, like vessels, hold and spill stories along the way, sometimes accidently, other times deliberately. Follow the clues..." Notes

1.Hank Bull, "DictatiOn: A Canadian Perspective on the History of Telematic Art", in Judy Malloy, ed., Social Media Archeology and Poetics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016. pp. 127-138, 133.

In Retrospect: P ublished in 1984, long before the social-media infused infosphere became a part of everyday life, Art Telecommunication, with its multi-lingual text, conceptual black and white and shades of gray images, and its combination of artist's statements, original documentation, and the words of critics, is an iconic work that --- with seminal theory, futurist prediction, and the lineage of networked art practice -- supplements contemporary immersive social media.

Heidi Grundmann wrote the introduction and created an information-dense concluding "Projects" section. "Projects" includes documentation of I.P. Sharp's ARTEX (Artists' Electronic Exchange); documentation of the 1980 Artists Use of Telecommunications Conference, which was organized by La Mamelle/Art Com at the San Francisco Museum of Museum of Modern Art and produced by Bill Bartlett; and documentation of Robert Adrian X's The World in 24 Hours, which connected artists in 16 cities on 3 continents for 24 hours; as well as Hank Bull's notes on telefonmusik and other projects by WIENCOUVER, "an imaginary city hanging invisible in the space between its two poles: Vienna and Vancouver." [1] In answer to a question from content | code | process about the book's contemporary relevance, pioneer telematic artist Hank Bull noted that: "We have difficulty imagining the world before the Internet. It takes a material object, like this book, to remind us that there once was a time when unmediated physical contact between humans was the norm, when long distance travel was expensive, and when a conversation in text and image over distance felt like science fiction. Art + Telecommunication is such an object. Since its publication, this book has functioned as a benchmark against which to measure, not only the rapid evolution of media, but also the critical understanding of its impacts and implications for artists and for the world. The idealistic notions expressed here, of 'dispersed authorship,' the 'noosphere,' and 'Indra’s Net' were tempered by the suspicion that contained within the technological acceleration of globalization lay the threats of surveillance, cultural homogenization, exclusion and social control. The authors were acutely aware that their book was being published in 1984. These texts are not only a fixed document of their time, like a fossil, but continue to resonate now, as alive (or not) as the network itself. Multi-Language Participation on the Global Internet "LexsSor System überträgt Bücher von Künstlern, Seite nach Seite und in Farbe. Genau wie beim Telefonieren konnten die LexsSor Teilnehmer irgendeines von 9.500 Künstlerbüchern in dem Archiv einfach anwahlen. " "The LexsSor system transmits artists' books, page by page in colour. As easily as telephoning, LexsSor owners could dial any of the 9500 artists' books in the archive." "LexsSor transmet les livres des artistes, page par page et en couleurs. Les usagers du système peuvent ainsi consulter les quelque 9 500 ouvrages des archives." - Eric Gidney in Art Telecommunication [2]

Setting the stage for a diverse networked culture of the future, 30 years ago, Art Telecommunication used an innovative approach to publishing in multiple languages. Today, the increasing number of languages represented on the Internet could auger a widening of filter bubbles to include International content -- I now have French, German, Spanish and Catalan in my Twitter stream -- and subsequently a greater need for the study of languages. In 2017, although English is still the dominant language on the Internet -- with 985 million users, according to Internet World Stats -- that represents only 25.3% of Internet users. English is followed by Chinese, with 771 million users (19.8%); Spanish is third, with 312 million users (8%); and Arabic is fourth, with 185 million users (4.8%)." [5] Documenting Networked-Situated Projects "It is physically impossible to experience networked projects that are simultaneously produced in separate locations other than as versions: The project as a whole eludes human perception. This aggravates the already serious problems of documentation and interpretation common to all fugitive, process- or time-based art projects, with the unfortunate result that many distributed telematic projects have been insufficiently documented and hardly interpreted at all. -- Heidi Grundmann, in At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet [6]

"Hall of Whispers takes its name from an ancient Babylonian myth of a specially constructed room in one of the ziggurats where a whisper would stay alive forever. I have an image of the electronic networks whispering ceaselessly with the voices of these times." [7] For such works, even if we begin to think in terms of X-reality as increasingly blurring the distinction between virtual and physical, [8] "presence" remains an issue, since at the time of creation of a social media-based narrative, not everyone with potential access will be logged on. "One of the first things I observed," Robert Adrian notes in a 2009 interview with Dieter Daniels, "is that there is no audience for this. You're either a participant or you're not there." But, perhaps, because he is saying this relatively recently, in a time where the large amount of people in contemporary social media environments has altered the early artist-to-artist experience of networked narrative, he continues by saying: "There is no longer an artist-audience relationship; the artist somehow disappears into the audience and vice-versa, so it becomes a participatory environment." [9] For example, in Teju Cole's 2014 Twitter-based Hafiz -- where other Twitter users tweeted Cole's story as if they were themselves witness to a traumatic event -- there was a writer, Teju Cole; there were members of the audience who actively participated as actors; and there were other people, who, by the act of following Cole on Twitter, were a part of the participatory environment. If this were a real-time performance, photographs would be expected. Interviews of the audience might also be of interest, but, reproducing tweets does not convey the real-time experience of Hafiz, and, outside of the active participants, it might be difficult to identify who on Twitter was "there". Documentation of transmedia works created on multiple platforms also creates difficulties. They are multiplied as we grapple with the differing ways in which users may have followed an interface. "Instead of the artwork as a window onto a composed, resolved, and ordered reality, we have at the interface a doorway to undecidability, a data space of semantic and material potentiality," Roy Ascott observes in his classic essay "Is there love in the telematic embrace?" [10] As Jay Bushman, transmedia producer for The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, notes: "There are limited toolsets - thank Zod for Storify - that can help in some cases, but they are usually limited to small scale compilations, or to single platforms. They do not scale for multi-voiced, multi-format, multi-platform stories. For example, The Lizzie Bennet Diaries sprawled across 35 individual social accounts on a dozen platforms. Social platforms are already not great at helping you find something that happened last week, last month or last year, and it's almost impossible to find an old story if the pieces of it are spread across multiple sites." [11] Bushman created a chronological list of links for The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, but recreating the original audience experience was elusive. His company, The Horizon Factory, proposed (but did not find funding for) compiling social and interactive video, audio, text, graphics, and associated media and information into an app that would serve as a single package. Although, for the most part, they were not documenting social-media distributed narrative, a contingent strategy was effectively used by Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop, who not only published the Pathfinders project in a scalar edition that documented early work in electronic literature with video interviews, video traversals, text, images and audio, [12] but also created the 2017 MIT Press book Traversals in conjunction with Pathfinders. [13] One aspect of the relevance of their process is discussed by Joseph Tabbi in his introduction to Traversals, where he writes: "...what's said about the works in reviews and scholarly essays is no longer kept physically separate from the works: a scholar's essay and a reader's discussion now appear mostly in the same medium as the work as the work itself, and the commentaries can be accessed along with the work's versionings. All are gathered on a common writing space..." [14] "... Everybody is asking questions. But what I think is very important, if one is interested at all in culture and what culture is, that strategies be developed for different groups forming again and again for the purpose of realising different projects or whatever you may call the different frames from which people work, certain aspects of the question 'how is our culture changing now?'." -- Heidi Grundmann in an interview with Josephine Bosma [15] Heidi Grundmann's Art Telecommunication does not provide a simple answer to the issue of documenting contemporary social-media based narrative in a different era of art practice. Nevertheless, in addition to its iconic representation of 1970's and early 1980's creative networked projects, it opens a door to innovative documentation and in the process suggests contemporary strategies. Given the central role of social media in contemporary lives, exploring the possibilities not only of creating but also of documenting social media-based works of cultural significance is an important issue.

_______________________________

1. Hank Bull, "WEINCOUVER" in Heidi Grundmann, ed., Art Telecommunication. Vancouver: Western Front; Vienna: BLIX, 1984. p. 123. 2. Eric Gidney's description of the conceptually proposed artists book delivery system conceived in circa 1981 by Steve s'Soreff, editor of the Avant Garde Art Review is in ibid, p. 12. 3. See the correspondence from Robert Adrian in the transcript of La Plissure du Texte in Telematic Connections: The Virtual Embrace, Walker Art Center, 2001. Curated by Steve Dietz. 4.Bruce Breland, ibid. 5.Internet World Stats, "Internet World Users by Language - Top 10 Languages", June 2017. 6.Heidi Grundmann, "REALTIME- Radio Art, Telematic Art, and Telerobotics: Two Examples", in Annmarie Chandler and Norie Neumark. eds., At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2006. pp.314-334,323-324. 7. Brian Andreas, "Hall of Whispers", in Judy Malloy, ed., Making Art Online, in Telematic Connections: The Virtual Embrace, Walker Art Center, 2001. Curated by Steve Dietz. 8. In Hello Avatar, Rise of the Networked Generation, the history and issues of online identity, MIT Press, 2011) scholar and electronic music composer Beth Coleman defines X-reality in this way: "X-reality describes a world that is no longer distinctly virtual or real but, instead, representative of a diversity of network combinations. With X-reality, I mark a turn toward an engagement of networked media integrated into daily life, perceived as part of a continuum of actual events. This is a movement away from computer-generated spaces, places, and worlds that are notably outside of what we might call real life and a transition into a mobile, real-time, and pervasively networked landscape." (pp 19-20) 9. Robert Adrian's words are quoted on an unnumbered page that opens the body of Daniels, Dieter and Gunther Reisinger, eds., Net Pioneers 1.0: Contextualizing Early Net-Based Art, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010. 10. Roy Ascott, "Is their love in the telematic embrace?" in Ascott, Roy, Telematic Embrace : Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, edited and with an essay by Edward A. Shanken. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007. pp. 232-246 , 237. This essay was first published in Art Journal in 1990. 11. Jay Bushman, "The Lizzie Bennet Diaries", in Judy Malloy, ed., Social Media Narrative: Issues in Contemporary Practice, hosted by The Rutgers Camden Digital Studies Center and Judy Malloy and the Rutgers Camden DSC Class in Social Media Narrative: Lineage and Contemporary Practice Facebook, November 16 - 21, 2016. 12. Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop, Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature, USC Scalar, 2015. Funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. 13. Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar, Traversals: The Use of Preservation for Early Electronic Writing. MIT Press, 2017. 14. Joseph Tabbi, "Foreword" in ibid, ix-xiv, xi. 15. Josephine Bosma, "Interview with Heidi Grundmann", Telepolis, August, 1997.

reviewed by Judy Malloy C irculated in Italy and France, (and beyond) in the middle ages, theory composers' treatises, such as Guido d'Arrezzo's Micrologus, established a enduring framework for the composition of music. Contingently, pre-web composers of literary hypertext, such as Michael Joyce and Stuart Moulthrop, were working in parallel with the work of researchers and theorists, including Mark Bernstein, Jay Bolter, Jane Yellowlees Douglas, George Landow, and Cathy Marshall,[1] some of whom, Jim Rosenberg, for instance, were/are themselves theory composers in that they not only wrote literary hypertext but also codified hypertext theory and practice. But in the environment of a grand, accessible, ubiquitous hypertext platform, the World Wide Web, creative hypertext writing is increasingly approached intuitively (or with routine applications) without knowledge of hypertext lineage or theory. This is not necessarily problematic given that there are differences in web-based hypertext and classic pre-web literary hypertext. Nevertheless, the publication of Jim Rosenberg's Word Space Multiplicities, Openings, Andings clearly reminds us that there is no reason to assume that our understanding and use of hypertextual systems cannot be enriched. Furthermore, at a time when in response to fluctuating authoring system availability, writers and students are exploring the creation of personal authoring systems, the papers in Word Space Multiplicities, Openings, Andings -- published in the Computing Literature series under the editorship of Sandy Baldwin, Director of the Center for Literary Computing at West Virginia University -- open new ways of considering both the composition of and the writer/reader experience of hypertext literature. The opening sections of Word Space Multiplicities -- including Sandy Baldwin's "An Interview on Poetics", "A Conversation with Jim Rosenberg on the Interactive Art Conference on Arts Wire" and Rosenberg's Leonardo-published "Words on Works" riff: "The Word the Play Attaching at a Wide Interval" -- introduce his background, vision and composing process and set the stage for his formal papers. However, rather than review the opening "Essays and Interviews", in light of the mission of content | code | process, this review concentrates on the "Formal Papers" that comprise the second part of this slim but potent compendium. As we approach the composition of contemporary works that reside on the World Wide Web, the pedestrian use of links becomes a meaning-laden process in the light of Word Space Multiplicities. For instance, in his chapter "Locus Looks at the Turing Play: Hypertextuality vs. Full Programmability", Rosenberg explores algorithmic behavior in hypertext nodes and links including user/algorithm relationships and behavioral versus structural points of view. Along the way, he explores creative practice, such as the use of guard fields to control access to linked contents, and addresses creative writer-specific utilization of algorithmic behavior: "Classical hypertext algorithms have a clear identity: the user knows what is supposed to happen; indeed it would be taken as a sign of bad design if the user were not to know what is supposed to happen. But in the literary world, incomplete knowledge on the part of the reader has been an age-old artistic variable -- the novel derives much of its power precisely from the fact that the reader doesn't know what is going to happen. In generalized cybertexts it may be artistically important for the author not to spell out the identity of the algorithm. The author may or may not want the algorithm itself (e.g. source code) to be accessible; the author may or may not want the reader to know whether a particular phenomenon occurred as the result of an algorithm."[2]

Interactive poetry pioneer Jim Rosenberg has been working with non-linear poetic forms since 1966. His visually elegant, word-dense, compressed writer/reader-revealed spatial hypertexts -- including Intergrams and The Barrier Frames and Diffractions Through -- were published by Eastgate in the 1990's. In his words: "Somewhere along about '86 or so, playing with bit-mapped graphics and a mouse, I realized that software provided me a way of doing something I had wanted to do very much from the very start: word clusters -- putting words literally on top of one another. When words are put on top of one another visually, or aurally, the result often is that they interfere with one another to the point of unintelligibility. With interactive software, the words can be put atop one another and then by using the mouse, the reader can reveal individual layers one at a time, so all the words are intelligible..." [3] To completely experience his interactive work, it is important to run it, and much of his work is now available on his website at http://www.inframergence.org/jr/index.shtml T he formal papers that form the body of Word Space Multiplicities, such as "Hypertext in the Open Air" and "Locus Looks at the Turing Play", are core reading for writers of electronic literature. Even for those of us who have been working in the field for years and have read all these papers separately many times, the detail-intensive original thinking in Jim Rosenberg's papers is an extraordinary starting/restarting point for writing and programming with contemporary hypertext systems. For example focusing on the implementation of his Frame Stack Project [4] as actual working code, in "Hypertext in the Open Air: A Systemless Approach to Spatial Hypertext", Rosenberg deftly combines an exploration of his own authoring process with issues such as run-time behavior in conjunction with authoring, and relatedly, interactive authoring and the affordances of spatial (visually structured) hypertext. In his primary paper, "The Structure of Hypertext Activity", Rosenberg establishes a vocabulary of acteme/episode/session, and in the process brilliantly clarifies the hypertext experience for both writer and reader. An acteme, in his definition, is an activity, such as the following of a link, whether it is one link or from a menu of links. An episode is defined as "whatever group of actemes cohere in the reader's mind as a tangible entity". [5] A session? "There is a clear break in hypertext activity when the user quits." [6] As regards the integrity of the episode, Rosenberg refers to Landow's admonition not to strand the reader in an episode dead-end where no inviting links occur, [7] but he also looks at this issue in terms of writer strategy, suggesting that composers of hypertext: "(1) be conscious of where these places are; (2) be aesthetically comfortable with them; (3) understand how you expect episode foraging experiences to work when the reader hits them; (4) understand how the reader might come out of the episode foraging experience." [8]

Reconstructing a hypertext episode, whether for critical writing or for presentation is fraught with peril. There is always that moment when you cannot remember which links you followed or in Interactive Fiction, whether you went north or northwest when you exited the abandoned house. In Word Space Multiplicities, best case user interfaces are suggested as Rosenberg looks at how a reader's episode might be documented and points to to a need for writers to provide ways in which to do this within the software. An automatic "gathering interface" would be, as he points out, especially desirable. In addition to published work of early music theory composers, it is likely that in the late middle ages, there was much unpublished yet influential knowledge that contributed to the development of musical composition. Contingently, in electronic literature early practitioner-informed theory and practice -- papers presented at conferences, broadsides distributed via Usenet groups, virtual discussion, such as the "Software as Art" topic on Art Com Electronic Network, [9] and kitchen-talk, such as the informal TINAC meetings [10]-- either was not documented or the documentation is no longer extant or not easy to access. On the rare occasions when a book such as Jim Rosenberg's Word Space Multiplicities, Openings, Andings appears, the publication of the collected writing of a brilliant, experienced, and insightful electronic literature theory composer is a treasured gift. Notes 1. Because Rosenberg generously cites the work of hypertext theory and theory composer colleagues, Word Space Multiplicities also provides a good introduction to some of the body of work in this field. 2. Jim Rosenberg, Word Space Multiplicities, Openings, Andings, Morgantown, WV: Center for Literary Computing, 2015.p. 179 3. "A Conversation with Jim Rosenberg" by Anna Couey and Judy Malloy on the Interactive Art Conference on Arts Wire. in Rosenberg, 2015 p. 46. The complete conversation is available at http://www.well.com/~couey/interactive/jim.html The Interactive Art Conference was an online laboratory for focused discussion and production of interactive art founded by Anna Couey and Judy Malloy in 1993. Defining interactive art as: "involv[ing] exchange between is originator, work, and participants," the Interactive Art Conference hosted a virtual artist-in-residence program that provided artists a forum to discuss their work and their exploration of interactivity. Discussion topics covered a broad range of interactive art media, including computer mediated literature, social sculpture, art telecommunications, electronic art, artists books, public art, installation, and performance. The resulting conversations were informal, providing a snapshot in time of the approaches of new media artists to their work. It was housed on Arts Wire's conferencing system and was active until 1998.

4. The Frame Stack Project is "a user interface for overlaying word objects on top of one another, while still allowing them to be read legibly". See Rosenberg, 2015, 199

5. Rosenberg, 2015, 135

6. Rosenberg, 2015, 145

7. As regards not stranding the reader in an episode dead-end where no inviting links occur, Rosenberg cites: G. P. Landow, "Relationally encoded links and the rhetoric of hypertext", Hypertext '87 Proceedings, Chapel Hill, NC, 1987.

8. Such writerly trapping of the reader is akin to the places in Interactive Fiction, where locked in a room with an ax wielding troll and no way out, the reader is likely to exit or (if available) "undo" and begin the story again.

9. Art Com Electronic Network is described in

Judy Malloy, "Art Com Electronic Network on The WELL: A Conversation with Fred Truck and Anna Couey", in Judy Malloy, ed., Social Media Archeology and Poetics, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, in press, 2016. 10. TINAC is described by Stuart Moulthrop in Judy Malloy: "The History of Hypertext Authoring and Beyond: Interview with Stuart Moulthrop," Authoring Software, October 2011. Available at http://www.narrabase.net/stuart-moulthrop.html reviewed by Judy Malloy November 1,2 2015

Review: D. Fox Harrell, Phantasmal Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013 "Expressive computing system developers can create digital stories, poems, or games in which aspects of content, such as theme, plot, emotional tone, metaphorical expression, or imagery, can vary improvisationally with user interaction...In addition to the new meanings generated in each new single session, new meanings emerge from the contrast between multiple readings or play sessions. These new meanings can be composed in response (discrete or continuous) to user interaction."" [1]

In contrast, although there is energy in this seemingly never-ending struggle, creators of new media must constantly rise above evolving technologies and look to the meaning of the work as a whole. To this end, for those who work on the fertile borders of content and code, Fox Harrell's Phantasmal Media is required reading. In this fascinating book of shifting definitions, that in their very mutability illustrate an elusive concept, Harrell initially explores "phantasm", not only in new media but also in print, film, and music, pointing for instance to Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon, where "Meaning is constructed as a blend of the concrete knowledge that the event did take place and the shifting, conflicting reports given by the characters amid a cinematic forest scene dappled by shadow and light." [2] Contingently, he illustrates the use of phantasm in new media with Chameleonia: Shadow Play, created in Harrell's Imagination, Computation, and Expression Laboratory (ICE Lab) at MIT. Inspired by W.E.B. Du Bois's definition of "double consciousness", Chameleonia responds to gestures and environment and in the process transforms a user's avatar, while at the same time the avatar's shadow mutates differently -- confronting the user with a virtual environment where an individual's self-conception is different from the way that individual is viewed by society. As the book progresses through sections on "Subjective Computing", "Cultural Computing", and "Critical Computing", like the variety of works that are used to illustrate these concepts, the definition of "phantasm" is variable and elusive. But, to a certain extent, that is a point of Phantasmal Media, at least for this reader. "The importance of the concept of the phantasm to challenge conventional understandings of human experience can be expressed by a simple observation - much of what humans experience is real is based upon the imagination." [3] "Phantasms are products of the imagination that are constructed at the nexus between sensory-imagistic and conceptual thinking."[4] "The concept of phantasmal media is inspired by the balance between orchestrated form, improvised chaos, and political forthrightness in Charles Mingus's compositions, such as "The Original Fables of Faubus..." [5]

Phantasmal Media, then, is a contingent companion to Michael Joyce's Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. (University of Michigan Press, 1995) Both are notable for fluid prose that conveys the meaning of its subject with the echoing of the language and/or structure of computer-mediated art/literature. "Expressive epistemology design appreciates the possibilities of artists representing smaller-scale, individually subjective knowledge in ways that are amenable to generating striking, destabilizing, or otherwise expressive content. In other words, expressive epistemology design is about designing the ability of systems to prompt phantasms using data structures." [6] D. Fox Harrell is Professor of Digital Media & Artificial Intelligence in the Comparative Media Studies Program and Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT. Using interactivity, social critique, cross-cultural narrative, cognitive semantics, gaming, generative systems, and the social aspects of user-interface design, his work explores relationships between imaginative cognition and computation. In Phantasmal Media, beginning with a review of his own path to interactive narrative -- in search of ways "to algorithmically retell stories from multicultural perspectives" -- Harrell credits the influence of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, which "weaves together profound social critique, experimentation with prose style and narrative structure, imaginative (even borderline science-fiction) events, and verbal imagery". [7] As documented in his book, the process with which Harrell's own practice has evolved is of interest to fellow creators of new media narrative. For instance, named for West African storytellers who incorporate improvisation in their performances, Harrell's formative authoring system, GRIOT System, utilizes a combination of knowledge engineering, interactivity, and cultural identity, in conjunction with algebraic semiotics, Joseph Goguen's mathematical approach to meaning representation. In his chapter on "Expressive Epistemologies", Harrell describes in detail how GRIOT System generates "polymorphic" poems, such as "The Girl with Skin of Haints and Seraphs". And in the same chapter, he documents how subsequently the GRIOT System was used to create the Living Liberia Fabric, a multimedia memorial that utilizes an interface based on traditional West African Fabrics. The relevance of Phantasmal Media to computer-mediated aesthetic systems resides in Harrell's exploration of concepts, such as the potential of computational media to explore identity in unprecedented ways; to offer the reader parallel immersive paths; to conceal these paths or reveal them at intervals; to construct layered narrative in unexplored ways. In this exploratory era -- as those of us who create and teach new media strive to fully understand each other's work -- the paths that Phantasmal Media provides to the understanding of the creation of computer-mediated art and literature are one of the approaches that distinguish this brilliant book. Contingently, the importance of Phantasmal Media does not reside only in the examples of computer-mediated narrative with which Harrell illustrates this book. As is the user's prerogative in exploring new media, it resides also in the examples that we as scholars and practitioners ourselves imagine. For instance, to my mind came the search for the phantasmal Beast in Emily Short's Bronze; the language of classic-science fiction that pervades the metaphorical journey in Andrew Plotkin's Hoist Sail for the Heliopause and Home; the deftly woven telenovela-inspired narratives in Mark Marino's hyperfiction a show of hands; and the challenging cultural phantasms that underlie my polyphonic and generative hypertext epic, From Ireland with Letters. Indeed, the very point of Phantasmal Media is the "reality" of differing imaginations. And Harrell's own definition of expressive epistemology design, (quoted to introduce this section) invites differing visions in the creation of electronic literature and computer games. Notes 1. D. Fox Harrell, Phantasmal Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013. p. 53 2. Ibid. p. 25. 3. Ibid. p. 4. 4. Ibid. p. 32. 5. Ibid. The quote and its continuation are on p. 338. 6. Ibid. p 84. 7. Ibid. pp. xi-xii. reviewed by Judy Malloy

Review: Judith Donath, The Social Machine, Designs for Living Online, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014 J udith Donath's The Social Machine sets forth a clear, elegant, and continually interesting approach to the design, interface, and pleasurable interaction of/with online social environments. With a focus on innovative interface and design, The Social Machine is also of interest to writers and artists, who are interested in issues of design and metaphor in the creation of interfaces for electronic literature and new media art. In her words: "The online world may evolve into an extraordinary new form of human society, where people make discoveries collectively, produce important works, and form friendships and other connections at a vastly unprecedented scale. But it is not there yet. Humans are fundamentally sensory and social beings: for the online world to achieve its promise, we need to design interfaces that work with how we see and respond to the world around us." [1] Judith Donath is a Harvard Berkman Faculty Fellow and former director of the MIT Media Lab's Sociable Media Group. She is also an artist, whose work exploring aspects of social media has been shown internationally. In her Preface to The Social Machine, she credits the MIT Architecture Machine Group, ("ArcMac", the precursor of the Media Lab, where she began her graduate studies) for the genesis of the remarkable approaches to the social media environment that she sets forth in this book. At ArcMac, Donath was "immersed in a culture devoted to inventing technologies to transform how people think, learn and communicate." And many of the ideas in this book, she observes, spring from the ArcMac culture "...that emphasized the sensory experience of the computer interface, that it should not be a cramped read-out, but a fully inhabitable environment" [2] The Social Machine utilizes Donath's work -- including work created in collaboration with students and colleagues -- to explore creative approaches to contemporary social media. For instance, Visual Who (1995) was inspired by a trip to Japan, where (when feeling isolated) she would run @who to see who was online at the lab back home. To make @who more interesting, Donath eventually used data from the Lab mailing lists to construct an interactive, beautifully designed graphic interface that overlaps interests and identities and in the process creates a feeling of co-presence and community identity. Visual Who is thus an artist's interface for a community of friends and colleagues, and in this context elegantly mediates the experience: "In the middle of the day, the 'window' shimmered with people coming and going; late at night it was dark, with only the occasional user checking in." [3] Other works documented in The Social Machine expand the idea of social media and/or ask us to consider social media issues. For instance, in 2000, Donath, Karrie Karahalios, and Fernanda Viégas created the Visiphone, which -- with both abstract and meaningful components -- interfaced conversations among friends who wanted to communicate virtually while cooking and cleaning in the kitchen. For instance, Christine Liu and Donath's UrbanHermes, (2006) which allowed users in public places to display words or images on Sharp Zaurus PDAs woven into unisex messenger bags -- and encouraged other users with similar gear to respond to or retransmit the images -- blurred the boundaries between the real and the virtual. In the process, UrbanHermes functioned as a performance art work and as a way of looking at the experience of social media in a different context, while at the same time, it asked questions about the dichotomy of expanded community and privacy. "Interfaces Make Meaning" Classic interface approaches are likely to be centered on user-computer interaction. On social media platforms, however -- as if each platform is mediated by a party host who invites people, introduces people, inspires conversation, and creates an environment of comfort -- in addition to user-computer interaction, the interface mediates a virtual gathering of people.

In Chapter 3 -- pointing out the ways in which, with color, motion, metaphor, interactivity, and good design, interfaces have the potential to shape sensual meaning -- Judith Donath creatively explores how "Interfaces Make Meaning". The ideal design of new interfaces for social media interaction, she observes, takes into account not only the re-creation of face-to-face conversation but also the need to explore new kinds of experience that augment face-to-face interaction. And importantly, there is a difference between designing interfaces for office applications and designing interfaces for social media. Social media is not an office: "..it is a machine for playing games, making friends, reading news, and watching movies amid a virtual crowd of other users. People use it to keep up with a wide range of acquaintances, to see what others are doing, to participate in discussions, and to present a particular view of themselves to close friends and distant strangers. Making an intuitively useable interface for this world requires making the information accessible and navigable, delineating public areas versus private space, and enabling various channels of communication. At the same time, it needs to capture the feeling of being in a social space, not a filing cabinet." [4]

"Visualizing Social Landscapes", "Mapping Social Networks",

Other chapters address: "Visualizing Social Landscapes" -- in ways that include algorithmically generated maps of online communities; "Mapping Social Networks" -- mapping the relationships between a large number of people -- a wedding guest map, for instance; "Visible Conversations: Seeing Meaning Beyond Words", for instance Themail (2006) - a personal email visualizer created by Fernanda Viégas, Scott Golder, and Donath for individuals to visualize the continuing history of their lives through the centrality of email; Also of interest, among others, are chapters on "Data Portraits", "Constructing Identity", "Embodied Interactions", and "Privacy and Public Space". We approach social media for various reasons, to gather information, to widen our circle of friends or colleagues, to participate in a way of expression that is becoming central to our society. Seldom do we step back and look at the social media environment in a visual way, asking: what does this "place"-where-I-spend-my-time contribute to the aesthetic qualities of my environment? How could it be re-imagined to allow people to enter a virtual space that is not only intellectually stimulating but also continually visually interesting. In The Social Machine, Donath reminds us of the time spent online and asks us to consider the interfaces of social media systems and the ways we approach them. Her voice is eloquent; her writing is elegant; her deep involvement with social media is important. Notes 1. Judith Donath, The Social Machine, Designs for Living Online, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014. p. 6 2. Ibid. p. vii 3. Ibid. p. 4 4. Ibid. p. 45 reviewed by Judy Malloy

Jef Raskin: The Humane Interface A leading force in the conception and creation of the Macintosh project for Apple, computer scientist and musician Jef Raskin, (1943-2005) who conducted the San Francisco Chamber Opera Society and played the organ, was an apostle for the design of "humane" interactive user interfaces. Raskin believed that user interface -- the way the user communicates with the computer -- should be at the core of the design of computers of the future. His influential book, The Humane Interface, New Directions for Designing Interactive Systems, (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2000) is a combination of technical and approachable. Merging interface anecdotes and wisdom with detailed information on program design, such as the design of search applications, The Humane Interface is a useful resource for new media writers who create work that situates poetry, narrative, and visual elements in the context of interface design. Raskin expresses interface strategies that are seemingly simple yet are important. For instance, in discussing the need to consider the role of memory in interface design, he cautions that you can't assume that the user will remember what he or she has seen previously -- a familiar problem for every writer who works with the issue of how the reader will remember the revealed details of character and place. Indeed, questions considered in many of Raskin's discussions -- how the user remembers the interface, what he or she has to do to produce more text, how navigation strategies path the reader -- are of primary interest in the creation of new media literature. Among the issues the book addresses are: Visibility versus invisibility -- basically, if you can always see an interface device, it is visible. if you have to remember how to find and use it, it is invisible. Monotony -- whether or not different ways of doing the same thing are incorporated into the interface The time it takes for the user to understand the work Taking into account "habit formation" -- ie wouldn't it be better to give the user a way to undo mistaken commands, rather than asking such questions as "are you sure you want to...", which may be habitually answered "yes". These issues may not always be important in a work of new media literature, and in some e-literature, either the subverting of such principles underlies the poetics or the revealing of the interface or what the interface reveals contributes to the narrative tension. Thus interface maxims can serve to bring clarity to the issues of interface design while at the same time (to a new media writer) they suggest literary strategies. For instance, the observation that the reader absorbs the workings of the interface at the beginning of the work and then assumes that he or she will always be confronted with it, might be used in one way when narrative flow is important, but in some instances, a new media writer might wish to alter the interface to differentiate time frames or characters. In the Chapter on "Navigation and Other Aspects of Humane Interfaces", Raskin discusses "intuitive" and "natural" interfaces. Noting that "intuitive" tends to be defined by what the user is used to, he uses as an example Star Trek IV when the former officers of the Enterprise are transported to the 20th century. In one incident, Scotty picks up the mouse of a Macintosh computer and attempts to operate the computer by speaking into the mouse. "Computer..." Because what the user is accustomed to now drives interface design for many computer systems, Raskin also observes that designing for natural and intuitive interfaces can be detrimental, i.e. there is a conflict between creating something that actually works better and creating something that the user is accustomed to. The author's attitude to icons may not be well received by visual artists. Nevertheless his question -- wouldn't it be easier to use words than trying to guess or reveal what each little symbol means? -- has some resonance for contemporary desktops, and he provides colorful examples of how icons can be misinterpreted. His discussion of programming environments, in which he emphasizes the role of documentation in programming creation, is of interest to the contemporary field of literate programming. (Chapter 7 - "Interface Issues Outside the User Interface") Importantly, The Humane Interface is of interest as regards how a seminal figure in interface design looks at interface design. And all of Jef Raskin's points serve to remind new media artists and writers of the importance of interface. "An interface is humane if it is responsive to human needs and considerate of human fragilities," he writes. "If you want to create a humane interface, you must have an understanding of the relevant information on how both humans and machines operate. In addition you must cultivate in yourself sensitivity to the difficulties that people experience." Jef Raskin's The Humane Interface, New Directions for Designing Interactive Systems, is available from Amazon reviewed by Judy Malloy

Brenda Laurel:

The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design I nterface -- the way the reader (the "user" in computer technology) communicates with the work -- is a primary concern for creators of electronic literature, as well as for readers who want to adventure into new media fiction and poetry. Writers and artists may choose to subvert the principles of interface design, striving in some cases to challenge the reader. For instance, the interface design principle of "least surprises" might be important in a work of literature in which the content of the text is most important. On the other hand, unexpected surprises might be a consideration for writers and artists who design interface as an integral part of the work itself, rather than as a way of accessing an underlying work. However interface is approached, it is of interest to understand the foundations of interface design, whether we choose to use or subvert them. The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design is a classic work of Macintosh Interface design. Edited by theater and computers scholar and researcher Brenda Laurel, who was at the time a consultant to Apple Computer and later created Purple Moon software for girls, the book is a formative documentation of the time in history when personal computers were beginning to make new ways of reading and writing possible. Although the focus is early Macintosh interface, the book is very useful, not only from the perspective of classic interface design but also but also in the exploration of the evolving concept of "interface". For instance, the uses of conversation in interface design -- in particular the simulation of human/human conversation, as opposed to human/computer interaction that does not take this into account -- is addressed by Susan F. Brennan in "Conversation as Direct Manipulation, an Iconoclastic View". Her chapter includes a series of useful examples and discusses how they can be enhanced with graphics. In her chapter on "Interface Agents: Metaphors with Character", Brenda Laurel talks about the creation of character in terms of personifying interfaces -- using characters in the theatrical sense -- with a focus on the creation of interfaces for practical applications. Initially, the interface device of personified "agents" that assist computer users was not as widely used as anticipated -- perhaps because our relationships with our computers are one-on-one, and we may not always desire an intermediary, something that was not initially anticipated in the age of transition to the personal computer. However, in the 21st century age of Siri -- how this concept was translated into ideas of computer interface agents and guides is of interest. In "Guides: Characterizing the Interface", Tim Oren, Gitta Salomon, Kristie Kreitman, and Abbe Don discuss designing an interface for Grolier Electronic Publishing's The Americana Series: America 1800-1850. Fictional characters, represented by graphic images, were used to help young readers select the material most appropriate to their interests. "We are finding out as much about the way people want to receive content as we are about navigation," the authors note. "We have uncovered a lot about what engages in the interface, but we have also discovered that the interface is deeply intermeshed with the content." Other chapters of particular interest include: Ronald Baecker and Ian Small, "Animation at the Interface" Chris Crawford, "Lessons from Computer Game Design" Abbe Don, "Narrative and the Interface" Myron W. Kruger, "Videoplace and the Interface of the Future" S.Joy Mountford and William W. Gaver, "Talking and Listening to Computers" Michael Naimark, "Realness and Interactivity" Theodor Holm Nelson, "The Right Way to Think About Software Design" Tim Oren, "Designing a New Medium" Howard Rheingold, "What's the Big Deal about Cyberspace?" Gitta Salomon, "New Uses for Color" Rob Swigart, "A Writer's Desktop" "If it is to be like magical paper, then it is the magical part that is all important and that must be most strongly attended to in the user interface design," Alan Kay writes about the computer screen in his chapter "User Interface: A Personal View". Kay also looks at Marshall McLuhan's ideas on how the printing press changed the thought patterns of those who learned to read, observing that "What McLuhan was really saying was that if the personal computer is a truly new medium then the very use of it would actually change the thought patterns of an entire civilization." Brenda Laurel served as professor and founding chair of the Graduate Program in Design at California College of Arts from 2006 to 2012 and recently as an adjunct professor in the Computer Science Department at UC Santa Cruz. The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design was conceived of and technically supported by interface designer S. Joy Mountford and is available from Amazon reviewed by Judy Malloy. Last Update, October, 2018

The New Media Reader, E xploring interface development and in particular narrative and poetic uses of interface in new media literature in a continuing series on interface issues, Authoring Software looks at an important compendium for students and teachers of new media writing practice: The New Media Reader, edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003) A valuable collection of source documents -- presenting over 50 points of view of new media history in one volume and including a CD of seminal works -- The New Media Reader forges an original path through the contemporary history of new media up to the development of the World Wide Web. Introductory statements by Janet Murray and Lev Manovich and commentary throughout by the editors, introduce a collection of essays that range from Donna Haraway's influential A Cyborg Manifesto, to an historic introduction to the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee, Robert Cailliau, Ari Loutonen, Henrik Frystyk Nielsen, and Arthur Secret. " The playful construction within constraints that the Oulipo defined as the role of the author can become an activity extended to readers, who can take place in the interpretation, configuration, and construction of texts." From the point of view of writing that predated computer-mediated writing but experimented with proto-interface structures in print works, Six Selections by the Oulipo is one of the most interesting sections in The New Media Reader. Founded in France in 1960 by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais, the group's name is an acronym of Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, roughly translated: "workshop of potential literature". Setting the stage for the flowering of French works of digital literature in the 1980's when writers, including Jean-Pierre Balpe and Philippe Bootz, among many others, created works that were actually implemented on computers, Oulipo poets and writers experimented with the very structure of literature, using print and experimental artist book formats. Their writing is particularly interesting in that their strategies in print foresee reader interaction with literature and provide an interesting look at literary systems now implemented by authoring software. "The potential that lies within such an understanding of interactive experiences is a reconfiguration of the relationship between reader, author, and text," Nick Montfort and Noah Wardrip-Fruin write in their introduction to the Oulipo. "The playful construction within constraints that the Oulipo defined as the role of the author can become an activity extended to readers, who can take place in the interpretation, configuration, and construction of texts." Six Selections by the Oulipo begins with Raymond Queneau's One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems for which he wrote a series of sonnets -- 14 lines of structured poetry -- which are composed so that they can be combined in many different ways and are laid out so that lines can be cut put to reveal a very large number of different poems. The anticipation/the foresight to see how such an approach might be taken are at the core of the migration of experimental writing from print to new media. Queneau clearly saw this, not only in One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems but also -- running at the bottom of a series of pages in The New Media Writer -- in his Yours for the Telling in which the adventure story interface of branching paths is anticipated: "Would you prefer the tale of the three, tall lanky beanpoles if so go to 16 if not go to 3." Following One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, French poet Jean Lescure's "Brief History of the Oulipo" winds in and and out of the history and goals of the group in a diffuse poetic essay that itself reflects the qualities of the work of this group of poets and writers (of which Lescure was a member) and for whom literary history, the literary qualities of experimental literature. and an exploration/discovery of structure were core as was multiplicity of meanings -- "In short, every literary text is literary because of an indefinite quantity of potential meanings" he states. Other documents in this section of The New Media Reader include: Mathematician/writer Claude Berge's "For a Potential Analysis of Combinatory Literature",which begins with forerunners of now computer-mediated strategies in the humanities, such as Mozart's "Musical Game" that allowed people to compose variations on one of his works by combining a series of musical phrases. Berge then displays a -- particularly interesting from an interface point of view -- creative series of systems analysis graphs of literary works with experimental structures, including the work of Queneau and Raymond Roussel, as well as many other approaches that can be expressed with mathematical diagramming. The graphs themselves -- although in the spirit of Oulipo how they might be created differently could be considered -- are of interest to writers of new media literature, whosometimes struggle with ways to map out the structures of their works.

"Computer and Writer: The Centre Pompidou Experiment" Italo Calvino was also a member of Oulipo and is represented in this section by Prose and Anticombinatorics, a narrative with programmic solutions to a murder mystery. In addition to Oulipo, experimental writers in print whose work is featured in The New Media Reader include Jorge Luis Borges, William Burroughs writing on "The Cut Up Method of Brion Gysin", and Augusto Boal. " On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk." In a series of documents that review the contributions of information science futurists, The New Media Reader documents the history of contemporary creative organization of information with papers by Vannevar Bush, Alan Turing, Norbert Wiener, Theodor H. Nelson, and Douglas Engelbart, among many others. Many new media artists and writers created their work on separate but parallel tracks. Nevertheless, these papers are of continual interest --not only historically but also in formulating insights and ideas for future directions in the field. For instance, in 1945, observing that the human mind "operates by association", in his futurist paper "As We May Think", originally published in The Atlantic Monthly and reprinted in The New Media Reader, World War II Director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development, Vannevar Bush asks readers to: "Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and to coin one at random,"memex" will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books,records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory. It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk." In the following years, information specialists, such as Henriette Davidson Avram and Ralph H. Parker and many others, both designed and created vast systems of searchable computerized library catalogs that are not represented in this book. [1] These systems were the backbone from which branched (or were created on separate parallel paths) innovative uses of computerized full text information systems on which The New Media Reader focuses, such as the Evolutionary List File (ELF) system proposed in Ted Nelson's classic paper, "A File Structure for the Complex, the Changing, and the Indeterminate" (1965) in which Nelson quotes Vannevar Bush's definition of the memex, addresses the problems of organizing and accessing personal and scholarly information of scholars, and suggests an ELF system using a database based on entries, links, and lists. He coins the word hypertext and imagines full text information systems as containing not only words but also images and film. A primary use of his ELF system is scholarly writing, but he envisions other possibilities. Also of interest in The New Media Reader is Douglas Engelbart's Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework, as well as classic source documents in computer and information science history that include Ivan Sutherland's "Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System"; Richard Stallman's "The GNU Manifesto"; Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg's "Personal Dynamic Media"; and Stuart Moulthrop's "You Say You Want a Revolution? Hypertext and the Laws of Media".

" It is our hope that all courses in which The New Media Reader plays a role will include serious study of the digital objects presented here-or of other artifacts, online and off, that don't lend themselves to being reproduced on the printed page. New media cannot be grasped by only consulting firstary sources and critical writing, however important such perspectives may be. Whether our goals include insightful

analysis or meaningful new creation, our work should be grounded in interaction with specific new media creations --

as surely as those interested in literature should read literary works, as much as those interested in cinema should watch films." Outside of Eastgate's continuing importance in publishing hypertext literature and the Electronic Literature Organization's work in this area, early works of new media literature are not always easy to locate or to run. Thus, it is important that (although some selections require applications that may not be available to every reader) the CD that accompanies The New Media Reader contains a notable collection of interesting selections of pre-World Wide Web new media writing and games, beginning (as regards games and works of art) with Stephen Russell's legendary Spacewar! and also including Gregory Yob's Hunt the Wumpus, Adventure, Jim Rosenberg's Diagram Series 3 and 4, Judy Malloy's collaborative literary authoring system, You!, Robert Kendall's The Clue, poems by John Cayley, and Writing on the Hypertextual Edge, edited by Stuart Moulthrop, a section of the Spring 1991 issue of Writing on the Edge, which includes Izme Pass by Carolyn Guyer and Martha Petry, as well as Michael Joyce's WOE. " What McCloud's work nevertheless shows is that new forms, even those that have not been studied seriously for centuries or even decades, do indeed have certain conventions and rules, and that if the form being studied is considered with care and thought, these rules can be determined, benefitting those who work in the form, who are striving to improve the practice of their art." -- Nick Montfort As regards the creation of interface, The New Media Reader is particularly useful to new media writers in presenting an overall picture of historic approaches. The book also reprints quite a few papers that are specifically helpful to designers of interfaces for new media literature. They include: Richard A. Bolt, "'Put-That-There': Voice and Gesture at the Graphics Interface" Lucy A. Suchman, two excerpts from her book Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-machine Communication The first addresses navigation -- as an example of different approaches, contrasting European style navigation, which begins with a plan, with Trukese navigation which begins with an objective; the first addresses interactivity, which she approaches from a anthropology/sociology point of view that might inspire conceptions of how narrative can be differently considered for "interactive artifacts". Scott McCloud's "Time Frames" (from his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art) Brenda Laurel, "The Six Elements and Causal Relations Among Them" (from her book Computers as Theater) and "Star Raiders: Dramatic Interaction in a Small World" (from her PhD thesis) J. David Bolter, from his book Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Writing, a selection entitled "Seeing and Writing", which looks at the visual aspects of the "Electronic Page." Additionally, The New Media Reader hosts a series of papers that look at creative new media in learning environments. For instance telemative narrative pioneer Roy Ascott is represented with "The Construction of Change", an essay with a central focus on an education of artists that includes cybernetics. And Michael Joyce's "Siren Shapes: Exploratory and Constructive Hypertexts" focuses on classroom uses of StorySpace and hypertext. More information about , The New Media Reader is available on the MIT Press website at http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=9604 and on the book's website at http://www.newmediareader.com/index.html The Table of Contents is listed at http://www.newmediareader.com/book_contents.html

The CD Table of Contents is listed at reviewed by Judy Malloy Notes

1. Queens College CUNY,

Library Technology Timeline Also recommended as supplemental source material are publications about seminal art telecom systems, such as Heidi Grundmann, Editor, Art Telecommunication, Vancouver, Canada: Western Front; Wien, Austria: Blix, 1984 and Roy Ascott and Carl Eugene Loeffler, Guest Editors, Connectivity: Art and Interactive Telecommunications, Leonardo 24:2, 1991. For information about the content | code | process resource, email Judy Malloy at: jmalloy@well.com Suggestions for inclusion are welcome! last update December 1, 2017 |

New:

Heidi Grundmann

Jim Rosenberg

D. Fox Harrell

Judith Donath

Jef Raskin

Brenda Laurel

Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort, eds. |

Edited by cultural critic Heidi Grundmann, producer of KUNSTRADIO-RADIOKUNST, and published by Western Front in Vancouver, B.C. and BLIX in Vienna, Art Telecommunication (also known as Art + Telecommunication) epitomizes the aesthetic of late 1970's and early 1980s networked projects. Primary essays in this book are by Eric Gidney, Roy Ascott, Tom Sherman, and Robert Adrian X. In addition to their own work, their statements describe works by other artists, including the SEND/RECEIVE Project, Tom Klinkowstein's Levittown, and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz' Hole in Space.

Edited by cultural critic Heidi Grundmann, producer of KUNSTRADIO-RADIOKUNST, and published by Western Front in Vancouver, B.C. and BLIX in Vienna, Art Telecommunication (also known as Art + Telecommunication) epitomizes the aesthetic of late 1970's and early 1980s networked projects. Primary essays in this book are by Eric Gidney, Roy Ascott, Tom Sherman, and Robert Adrian X. In addition to their own work, their statements describe works by other artists, including the SEND/RECEIVE Project, Tom Klinkowstein's Levittown, and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz' Hole in Space.

Concerns about English language domination of global networks were present from the early years of telematic art. [3] In response, many of Art Telecommunication's pages are composed in lexia-sized translations of the same text in German, English, and French. These are the languages that best represent the artists documented in the book. For example, British artist Roy Ascott's ARTEX-based collaborative fairy tale, La Plissure du Texte originated from Paris, where Ascott played the Magician; the story was augmented at nodes which included, among others, Quebec, which played the Beast, Vienna, San Francisco, Sydney, Toronto, and Vancouver, which played the Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Prince was played by Bruce Breland, who observed as the text passed through his node in Pittsburgh at 17.04 15/12/1983 that "THE PRINCE REALIZED THIS WAS NO ORDINARY REALITY AND THE PRINCESS WAS NO ORDINARY PRINCESS. THE SKY STARTED TO QUICKEN IN ITS COLOR CHANGES. A SEA OF WORDS BEGAN TO TIUMBLE ON THE SKY... [4]

Concerns about English language domination of global networks were present from the early years of telematic art. [3] In response, many of Art Telecommunication's pages are composed in lexia-sized translations of the same text in German, English, and French. These are the languages that best represent the artists documented in the book. For example, British artist Roy Ascott's ARTEX-based collaborative fairy tale, La Plissure du Texte originated from Paris, where Ascott played the Magician; the story was augmented at nodes which included, among others, Quebec, which played the Beast, Vienna, San Francisco, Sydney, Toronto, and Vancouver, which played the Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Prince was played by Bruce Breland, who observed as the text passed through his node in Pittsburgh at 17.04 15/12/1983 that "THE PRINCE REALIZED THIS WAS NO ORDINARY REALITY AND THE PRINCESS WAS NO ORDINARY PRINCESS. THE SKY STARTED TO QUICKEN IN ITS COLOR CHANGES. A SEA OF WORDS BEGAN TO TIUMBLE ON THE SKY... [4]

A printout from La Plissure du Texte could be displayed unfolded in a museum case or pinned to a museum wall. However, the human connection and the performative energy, that occurred when this work was created, would be difficult to convey in this context. This is the case not only of other early telematic works, such as Bill Bartlett's 1979 Interplay, in which a dialogue on computer culture emerged from terminals in every participating city, but also of many 1990's networked projects, including Carolyn Guyer's collaborative, women-centered hypertext, Hi-Pitched Voices, and Brian Andreas' collaboratively-created Hall of Whispers:

A printout from La Plissure du Texte could be displayed unfolded in a museum case or pinned to a museum wall. However, the human connection and the performative energy, that occurred when this work was created, would be difficult to convey in this context. This is the case not only of other early telematic works, such as Bill Bartlett's 1979 Interplay, in which a dialogue on computer culture emerged from terminals in every participating city, but also of many 1990's networked projects, including Carolyn Guyer's collaborative, women-centered hypertext, Hi-Pitched Voices, and Brian Andreas' collaboratively-created Hall of Whispers: