In Retrospect:

Review of Heidi Grundmann, Art Telecommunication.

Vancouver: Western Front; Vienna: BLIX, 1984.

P ublished in 1984, long before the social-media infused infosphere became a part of everyday life, Art Telecommunication, with its multi-lingual text, conceptual black and white and shades of gray images, and its combination of artist's statements, original documentation, and the words of critics, is an iconic work that --- with seminal theory, futurist prediction, and the lineage of networked art practice -- supplements contemporary immersive social media.

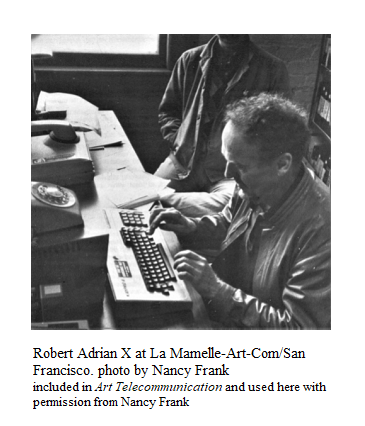

Edited by cultural critic Heidi Grundmann, producer of KUNSTRADIO-RADIOKUNST, and published by Western Front in Vancouver, B.C. and BLIX in Vienna, Art Telecommunication (also known as Art + Telecommunication) epitomizes the aesthetic of late 1970's and early 1980s networked projects. Primary essays in this book are by Eric Gidney, Roy Ascott, Tom Sherman, and Robert Adrian X. In addition to their own work, their statements describe works by other artists, including the SEND/RECEIVE Project, Tom Klinkowstein's Levittown, and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz' Hole in Space.

Edited by cultural critic Heidi Grundmann, producer of KUNSTRADIO-RADIOKUNST, and published by Western Front in Vancouver, B.C. and BLIX in Vienna, Art Telecommunication (also known as Art + Telecommunication) epitomizes the aesthetic of late 1970's and early 1980s networked projects. Primary essays in this book are by Eric Gidney, Roy Ascott, Tom Sherman, and Robert Adrian X. In addition to their own work, their statements describe works by other artists, including the SEND/RECEIVE Project, Tom Klinkowstein's Levittown, and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz' Hole in Space.

Heidi Grundmann wrote the introduction and created an information-dense concluding "Projects" section. "Projects" includes documentation of I.P. Sharp's ARTEX (Artists' Electronic Exchange); documentation of the 1980 Artists Use of Telecommunications Conference, which was organized by La Mamelle/Art Com at the San Francisco Museum of Museum of Modern Art and produced by Bill Bartlett; and documentation of Robert Adrian X's The World in 24 Hours, which connected artists in 16 cities on 3 continents for 24 hours; as well as Hank Bull's notes on telefonmusik and other projects by WIENCOUVER, "an imaginary city hanging invisible in the space between its two poles: Vienna and Vancouver." [1]

In answer to a question from content | code | process about the book's contemporary relevance, pioneer telematic artist Hank Bull noted that:

"We have difficulty imagining the world before the Internet. It takes a material object, like this book, to remind us that there once was a time when unmediated physical contact between humans was the norm, when long distance travel was expensive, and when a conversation in text and image over distance felt like science fiction. Art + Telecommunication is such an object. Since its publication, this book has functioned as a benchmark against which to measure, not only the rapid evolution of media, but also the critical understanding of its impacts and implications for artists and for the world. The idealistic notions expressed here, of 'dispersed authorship,' the 'noosphere,' and 'Indra’s Net' were tempered by the suspicion that contained within the technological acceleration of globalization lay the threats of surveillance, cultural homogenization, exclusion and social control. The authors were acutely aware that their book was being published in 1984. These texts are not only a fixed document of their time, like a fossil, but continue to resonate now, as alive (or not) as the network itself.

Multi-Language Participation on the Global Internet

"LexsSor System überträgt Bücher von Künstlern, Seite nach Seite und in Farbe. Genau wie beim Telefonieren konnten die LexsSor Teilnehmer irgendeines von 9.500 Künstlerbüchern in dem Archiv einfach anwahlen. "

"The LexsSor system transmits artists' books, page by page in colour. As easily as telephoning, LexsSor owners could dial any of the 9500 artists' books in the archive."

"LexsSor transmet les livres des artistes, page par page et en couleurs. Les usagers du système peuvent ainsi consulter les quelque 9 500 ouvrages des archives." - Eric Gidney in Art Telecommunication [2]

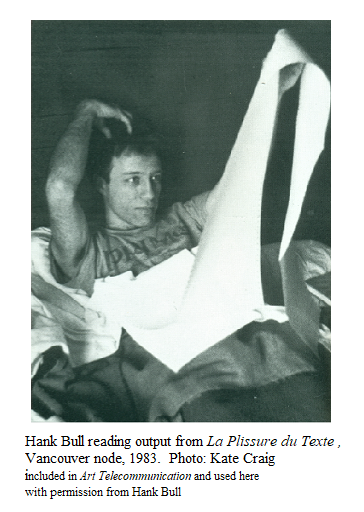

Concerns about English language domination of global networks were present from the early years of telematic art. [3] In response, many of Art Telecommunication's pages are composed in lexia-sized translations of the same text in German, English, and French. These are the languages that best represent the artists documented in the book. For example, British artist Roy Ascott's ARTEX-based collaborative fairy tale, La Plissure du Texte originated from Paris, where Ascott played the Magician; the story was augmented at nodes which included, among others, Quebec, which played the Beast, Vienna, San Francisco, Sydney, Toronto, and Vancouver, which played the Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Prince was played by Bruce Breland, who observed as the text passed through his node in Pittsburgh at 17.04 15/12/1983 that "THE PRINCE REALIZED THIS WAS NO ORDINARY REALITY AND THE PRINCESS WAS NO ORDINARY PRINCESS. THE SKY STARTED TO QUICKEN IN ITS COLOR CHANGES. A SEA OF WORDS BEGAN TO TIUMBLE ON THE SKY... [4]

Concerns about English language domination of global networks were present from the early years of telematic art. [3] In response, many of Art Telecommunication's pages are composed in lexia-sized translations of the same text in German, English, and French. These are the languages that best represent the artists documented in the book. For example, British artist Roy Ascott's ARTEX-based collaborative fairy tale, La Plissure du Texte originated from Paris, where Ascott played the Magician; the story was augmented at nodes which included, among others, Quebec, which played the Beast, Vienna, San Francisco, Sydney, Toronto, and Vancouver, which played the Sorcerer's Apprentice. The Prince was played by Bruce Breland, who observed as the text passed through his node in Pittsburgh at 17.04 15/12/1983 that "THE PRINCE REALIZED THIS WAS NO ORDINARY REALITY AND THE PRINCESS WAS NO ORDINARY PRINCESS. THE SKY STARTED TO QUICKEN IN ITS COLOR CHANGES. A SEA OF WORDS BEGAN TO TIUMBLE ON THE SKY... [4]

Setting the stage for a diverse networked culture of the future, 30 years ago, Art Telecommunication used an innovative approach to publishing in multiple languages. Today, the increasing number of languages represented on the Internet could auger a widening of filter bubbles to include International content -- I now have French, German, Spanish and Catalan in my Twitter stream -- and subsequently a greater need for the study of languages.

In 2017, although English is still the dominant language on the Internet -- with 985 million users, according to Internet World Stats -- that represents only 25.3% of Internet users. English is followed by Chinese, with 771 million users (19.8%); Spanish is third, with 312 million users (8%); and Arabic is fourth, with 185 million users (4.8%)." [5]

Documenting Networked-Situated Projects

"It is physically impossible to experience networked projects that are simultaneously produced in separate locations other than as versions: The project as a whole eludes human perception. This aggravates the already serious problems of documentation and interpretation common to all fugitive, process- or time-based art projects, with the unfortunate result that many distributed telematic projects have been insufficiently documented and hardly interpreted at all. -- Heidi Grundmann, in At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet [6]

A printout from La Plissure du Texte could be displayed unfolded in a museum case or pinned to a museum wall. However, the human connection and the performative energy, that occurred when this work was created, would be difficult to convey in this context. This is the case not only of other early telematic works, such as Bill Bartlett's 1979 Interplay, in which a dialogue on computer culture emerged from terminals in every participating city, but also of many 1990's networked projects, including Carolyn Guyer's collaborative, women-centered hypertext, Hi-Pitched Voices, and Brian Andreas' collaboratively-created Hall of Whispers:

A printout from La Plissure du Texte could be displayed unfolded in a museum case or pinned to a museum wall. However, the human connection and the performative energy, that occurred when this work was created, would be difficult to convey in this context. This is the case not only of other early telematic works, such as Bill Bartlett's 1979 Interplay, in which a dialogue on computer culture emerged from terminals in every participating city, but also of many 1990's networked projects, including Carolyn Guyer's collaborative, women-centered hypertext, Hi-Pitched Voices, and Brian Andreas' collaboratively-created Hall of Whispers:

"Hall of Whispers takes its name from an ancient Babylonian myth of a specially constructed room in one of the ziggurats where a whisper would stay alive forever. I have an image of the electronic networks whispering ceaselessly with the voices of these times." [7]

For such works, even if we begin to think in terms of X-reality as increasingly blurring the distinction between virtual and physical, [8] "presence" remains an issue, since at the time of creation of a social media-based narrative, not everyone with potential access will be logged on.

"One of the first things I observed," Robert Adrian notes in a 2009 interview with Dieter Daniels, "is that there is no audience for this. You're either a participant or you're not there." But, perhaps, because he is saying this relatively recently, in a time where the large amount of people in contemporary social media environments has altered the early artist-to-artist experience of networked narrative, he continues by saying:

"There is no longer an artist-audience relationship; the artist somehow disappears into the audience and vice-versa, so it becomes a participatory environment." [9]

For example, in Teju Cole's 2014 Twitter-based Hafiz -- where other Twitter users tweeted Cole's story as if they were themselves witness to a traumatic event -- there was a writer, Teju Cole; there were members of the audience who actively participated as actors; and there were other people, who, by the act of following Cole on Twitter, were a part of the participatory environment. If this were a real-time performance, photographs would be expected. Interviews of the audience might also be of interest, but, reproducing tweets does not convey the real-time experience of Hafiz, and, outside of the active participants, it might be difficult to identify who on Twitter was "there".

Documentation of transmedia works created on multiple platforms also creates difficulties. They are multiplied as we grapple with the differing ways in which users may have followed an interface. "Instead of the artwork as a window onto a composed, resolved, and ordered reality, we have at the interface a doorway to undecidability, a data space of semantic and material potentiality," Roy Ascott observes in his classic essay "Is there love in the telematic embrace?" [10]

As Jay Bushman, transmedia producer for The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, notes:

"There are limited toolsets - thank Zod for Storify - that can help in some cases, but they are usually limited to small scale compilations, or to single platforms. They do not scale for multi-voiced, multi-format, multi-platform stories. For example, The Lizzie Bennet Diaries sprawled across 35 individual social accounts on a dozen platforms. Social platforms are already not great at helping you find something that happened last week, last month or last year, and it's almost impossible to find an old story if the pieces of it are spread across multiple sites." [11]

Bushman created a chronological list of links for The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, but recreating the original audience experience was elusive. His company, The Horizon Factory, proposed (but did not find funding for) compiling social and interactive video, audio, text, graphics, and associated media and information into an app that would serve as a single package.

Although, for the most part, they were not documenting social-media distributed narrative, a contingent strategy was effectively used by Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop, who not only published the Pathfinders project in a scalar edition that documented early work in electronic literature with video interviews, video traversals, text, images and audio, [12] but also created the 2017 MIT Press book Traversals in conjunction with Pathfinders. [13] One aspect of the relevance of their process is discussed by Joseph Tabbi in his introduction to Traversals, where he writes:

"...what's said about the works in reviews and scholarly essays is no longer kept physically separate from the works: a scholar's essay and a reader's discussion now appear mostly in the same medium as the work as the work itself, and the commentaries can be accessed along with the work's versionings. All are gathered on a common writing space..." [14]

"... Everybody is asking questions. But what I think is very important, if one is interested at all in culture and what culture is, that strategies be developed for different groups forming again and again for the purpose of realising different projects or whatever you may call the different frames from which people work, certain aspects of the question 'how is our culture changing now?'." -- Heidi Grundmann in an interview with Josephine Bosma [15]

Heidi Grundmann's Art Telecommunication does not provide a simple answer to the issue of documenting contemporary social-media based narrative in a different era of art practice. Nevertheless, in addition to its iconic representation of 1970's and early 1980's creative networked projects, it opens a door to innovative documentation and in the process suggests contemporary strategies. Given the central role of social media in contemporary lives, exploring the possibilities not only of creating but also of documenting social media-based works of cultural significance is an important issue.

_______________________________

Notes

1. Hank Bull, "WEINCOUVER" in Heidi Grundmann, ed., Art Telecommunication. Vancouver: Western Front; Vienna: BLIX, 1984. p. 123.

2. Eric Gidney's description of the conceptually proposed artists book delivery system conceived in circa 1981 by Steve s'Soreff, editor of the Avant Garde Art Review is in ibid, p. 12.

3. See the correspondence from Robert Adrian in the transcript of La Plissure du Texte in Telematic Connections: The Virtual Embrace, Walker Art Center, 2001. Curated by Steve Dietz.

4.Bruce Breland, ibid.

5.Internet World Stats, "Internet World Users by Language - Top 10 Languages", June 2017.

6.Heidi Grundmann, "REALTIME- Radio Art, Telematic Art, and Telerobotics: Two Examples", in Annmarie Chandler and Norie Neumark. eds., At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2006. pp.314-334,323-324.

7. Brian Andreas, "Hall of Whispers", in Judy Malloy, ed., Making Art Online, in Telematic Connections: The Virtual Embrace, Walker Art Center, 2001. Curated by Steve Dietz.

8. In Hello Avatar, Rise of the Networked Generation, the history and issues of online identity, MIT Press, 2011) scholar and electronic music composer Beth Coleman defines X-reality in this way: "X-reality describes a world that is no longer distinctly virtual or real but, instead, representative of a diversity of network combinations. With X-reality, I mark a turn toward an engagement of networked media integrated into daily life, perceived as part of a continuum of actual events. This is a movement away from computer-generated spaces, places, and worlds that are notably outside of what we might call real life and a transition into a mobile, real-time, and pervasively networked landscape." (pp 19-20)

9. Robert Adrian's words are quoted on an unnumbered page that opens the body of Daniels, Dieter and Gunther Reisinger, eds., Net Pioneers 1.0: Contextualizing Early Net-Based Art, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010.

10. Roy Ascott, "Is their love in the telematic embrace?" in Ascott, Roy, Telematic Embrace : Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, edited and with an essay by Edward A. Shanken. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007. pp. 232-246 , 237. This essay was first published in Art Journal in 1990.

11. Jay Bushman, "The Lizzie Bennet Diaries", in Judy Malloy, ed., Social Media Narrative: Issues in Contemporary Practice, hosted by The Rutgers Camden Digital Studies Center and Judy Malloy and the Rutgers Camden DSC Class in Social Media Narrative: Lineage and Contemporary Practice Facebook, November 16 - 21, 2016.

12. Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop, Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature, USC Scalar, 2015. Funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

13. Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar, Traversals: The Use of Preservation for Early Electronic Writing. MIT Press, 2017.

14. Joseph Tabbi, "Foreword" in ibid, ix-xiv, xi.

15. Josephine Bosma, "Interview with Heidi Grundmann", Telepolis, August, 1997.

reviewed by Judy Malloy

Networked Art Works: in the Formative Years of the Internet

Judy Malloy: Introduction

Early Telematic Projects

Interview with Tom Klinkowstein

Poietic Generator

Interview with Olivier Auber

Marcello Aitiani: Nave di Luce (Ship of Light)

Nancy Paterson: Stock Market Skirt

Projects Nurtured in Online Conferences

Fred Truck: Independent Work: 1985 to 1995

Robert Edgar: Memory Theatre One

Anna Couey and Judy Malloy:

The Arts Wire Interactive Art Conference

Reviews

Review in retrospect:

Heidi Grundmann's Art Telecommunication

Review: Serge Guilbaut, Joni Low, and Pan Wendt:

Hank Bull: Connexion

Networked Art Works in the Formative Years

of the Internet is an

ongoing supplement to

the MIT Press Book:

Social Media Archeology and Poetics